Highlights

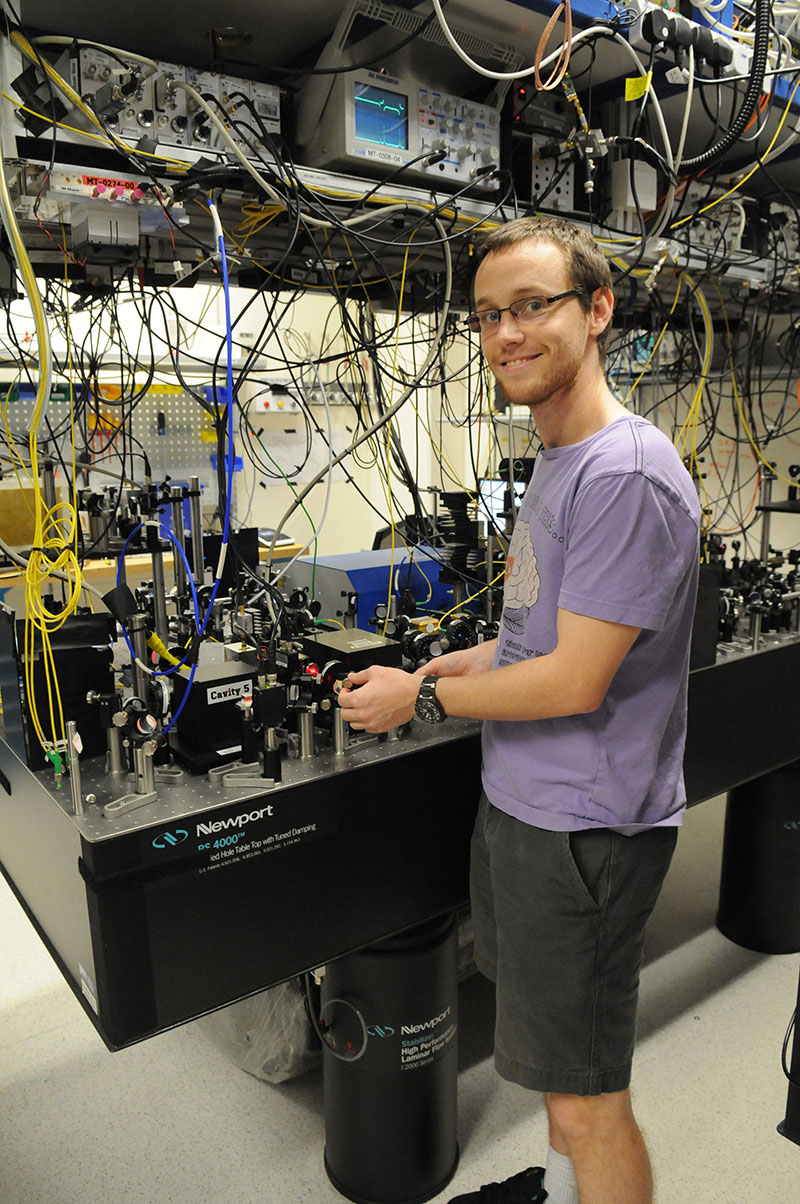

Meet a CQTian: Nick Lewty

Nick Lewty, who is soon to complete his PhD at CQT, helped make the world's most precise measurement of an atom's octupole moment.

Who are you and where are you from?

I'm Nick Lewty and I'm from the UK, from near a city in Northern England called Leeds. I'm 28.

What made you interested in quantum physics?

I had done my undergraduate studies at Leeds University and took a course there by Vlatko Vedral – he now has a position at CQT. He knows how to sell physics and make quantum information very sexy! I became interested in the idea of trying to build a quantum computer. A dream for the field is realising a quantum computer in the next 10 to 15 years that's useful for solving real world problems like protein-folding.

How did you end up at CQT?

After my undergraduate degree, I joined a new group at Leeds to start a PhD doing experimental quantum stuff. After a while I didn't think it was going to work out, and so I started to look for other positions. I'd been on holiday with my parents once to Brisbane and we stopped in Singapore on the way for three days. I fell in love with the place and even said to my mum and dad that I want to live here. I found that Murray Barrett's group at CQT was working on things I was interested in. Murray was nice enough to pay for me to fly out and do an internship for three months, and I really enjoyed it. I came for the internship in October 2008 and joined as a PhD student in January 2009.

What is your PhD research about?

My original goal was to develop microcavities – basically very small boxes to trap light that you can implement around an atom. They're useful to build photon-atom interfaces to transfer quantum information between atoms and photons. Atoms are good as a memory for quantum bits and photons are good for transporting information between atoms. We actually work with ions – charged atoms – because they are easier to trap.

How small are these boxes?

You can make very small cavities on the tip of an optical fibre using a laser pulse to melt the tip of the fibre into a concave shape. They are a few micron in size – that's thousandths of a millimetre. I went to France in my first year to learn how to do it, but in the end the process was challenging and didn't give the results we expected, so Murray decided it wasn't worth pursuing. Our current cavity size is about a centimetre.

If you didn't pursue microcavities, what have you done?

I was kind of left with the question of what to do next. A postdoc from another group came for a visit and gave us an idea for making a measurement of the 'octupole moment' of an atom. We thought we had the expertise to do it easily and went ahead. Our measurement for Barium atoms is the most accurate in the world. The idea was to improve atomic structure calculations but our accuracy is more than was really needed. So our result is more a demonstration of capability that we've got very good control over our trapped ion.

What for you are the highs and lows of the job?

I enjoy the building part of it, and that's good because the experiment was just setting up when I joined. They had two lasers then and now there are 15. The hands-on-work is electronics, optics, some basic computer programming and some machining. I actually find the experiment part – where you sit down and shine your lasers at your atom over a three month period and then you check everything – quite tedious!

Nick also brews beer.

What will you do after your PhD?

I'm due to finish by next January. I did want to stay in physics but I've come to think that I am not a strong enough all-rounder. I will probably go back to the UK and set up a brewery. I really like living in Singapore but there is a bigger market for this kind of thing in Britain and the setup costs, particularly for building rental, will be less. I also know there will be another three nanobreweries opening in Singapore soon, and we would be behind the competition.

Are we talking about brewing beer?

Yes. I started brewing here in September 2010 with my flatmates. Now it's me and Markus Baden, another CQT PhD student. You are legally allowed to brew up to 23 litres a month. There is a Singapore home-brewers gathering each month where we taste each other's beers and comment to help each other improve.

You can split people into two categories: people who do kits and the ones who do it all from raw ingredients, which is harder work. That's called all grain and it's the only way you can really make good beer. I've been doing all grain for over a year. My favourite beer so far was a summer ale, with fruity characteristics that came from the hops I used.

So this is a departure from physics?

Well, we have applied technologies we learnt in our PhD. Markus used his programming skills and I used my mechanical and electrical skills to make a temperature controller for a freezer so we could keep it anywhere from -5 up to 20 degrees. Then we made a temperature controller for an electric heater so that we could control the temperature of water between 30 degrees and boiling, so that we could do the beer making part that's called the wort.