Highlights

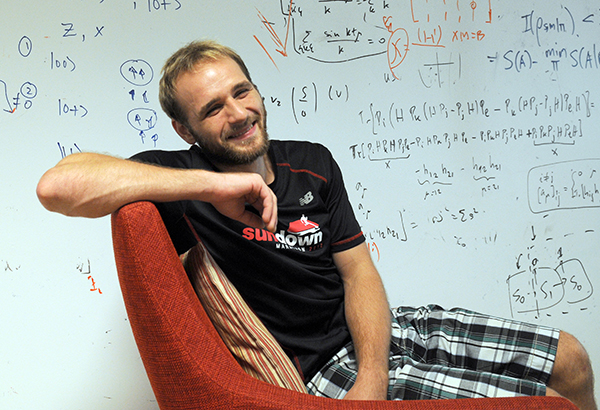

Meet a CQTian: Jed Kaniewski

"Quantum information being an interdisciplinary and relatively new field is very appealing to young people. You do not need to read 50 years' worth of papers to get to the frontier," says Jed, who joined CQT as a PhD student in 2012.

Who are you and where are you from?

My name is Jed Kaniewski. I was born in Warsaw, Poland in 1987.

How did you become a quantum physicist?

My undergraduate degree is actually in chemistry, my Master's is in applied mathematics and at the moment I am working on the boundary of physics, computer science and maths so calling myself a quantum physicist would be an oversimplification. But that is exactly the reason why I am here — quantum information being an interdisciplinary and relatively new field is very appealing to young people. You do not need to read 50 years' worth of papers to get to the frontier and a lot of simple, natural problems remain relatively unexplored.

What is your research about?

I work on cryptography, which is the study of how to exchange and process information in a secure fashion, i.e. keeping it secret from an adversary. It turns out that the quantum world is strictly richer than the classical, everyday world. Certain tasks that we know are impossible classically become feasible when we start to take advantage of quantum effects.

The simplest and most successful example is the quantum key distribution protocol. Suppose that Alice and Bob are trying to exchange a secret but they are forced to do it in a public place, where they have no privacy. Intuitively this is a difficult task, and indeed one can show that classically it's not possible unless we make some extra assumptions. On the other hand, by sending quantum systems Alice and Bob can exchange a secret in such a way that if their protocol succeeds, they are guaranteed that nobody else has learnt it. This is what we call security guaranteed by the laws of physics.

What is something you do outside of work?

I spend most of my day sitting down in front of my computer so I occupy the rest of my time with various physical activities. It turns out that South-East Asia is a great place for rock-climbing, and that became my main hobby when I moved to Singapore.

In Singapore we train on artificial walls, but any long weekend is a good excuse to go to Thailand, Malaysia or Hong Kong to go on the real rock. I also took up long-distance running — I especially liked the Sundown Marathon. It starts at midnight and you run through the night. It is a great experience to be part of a 20 000 people crowd running through the city centre in the middle of the night.

On long weekends, Jed exchanges physics problems for the physical challenge of climbing the rock-faces of South-East Asia.

What's good about your job?

I like the freedom and flexibility of being a PhD student — I can choose what problems I want to work on, who I collaborate with and which conference I attend. I also like the fact that if I feel like learning a new bit of maths or science, I can take my time and do it — it is part of my job.

Last year I took part in a summer school in Canada for students in quantum information. Having over a hundred young people from all over the world in the same place for two weeks was a great opportunity to socialise in situations ranging from classes taught by professors to mixed, free-for-all football sessions. Such events contribute to the friendly atmosphere in the community. When you go to a conference or a workshop you are very likely to meet some people you already know, which makes everything much more enjoyable.

What is hard?

Lack of progress is hard. Sometimes you find yourself working on a problem for quite some time but you get no results. You try to tackle it from different angles, using different techniques and approaches but you are still getting nowhere. That is hard and makes you think about putting the project aside. It is like attempting a climbing route that you cannot finish — it is always a tough decision and it does not feel good but at least you have given it a try. But getting out of the comfort zone is part of the job — even the greatest researchers have folders full of notes on problems they tried but did not manage to solve.

What is your biggest dream for your field of science?

I think that for most theoretical scientist the dream is to see their theory put to work. I would love to see real devices doing quantum cryptography. For certain applications, e.g. generating random numbers or generating a secret key, such devices already exist but for others, such as authentication, this is still ahead of us.